The Australian Magazine 53 November 18 – 19 2000

Fanita Clark reflects after the memorial service for her son Jason at the Gold Coast’s Broadbeach, just one of the places he loved to surf.

Australia’s suicide rate exceeds our road toll, yet little has been done to redress it.

One victim’s mother began her own campaign of awareness.

WASTED LIVES

Story Matt Thrower – photography Andrew Merry

|

Above: Wreaths laid at the service, in the shadow of the Top left: A mourner at the Broadbeach memorial service. Left: Fanita Clark’s son, Jason. |

Fanita Clark’s Brisbane house is a typically neat, comfortable suburban home with photos on the mantelpiece – each showing a smiling, seemingly contented and carefree family. There is also a school formal photograph of her teenage son Jason, a handsome young man with long, blond hair, wearing a tuxedo and grinning happily. He looks the perfect picture of youthful health and vitality.

But on May 29, 1999, Jason Clark, then 19, put himself in the path of an oncoming train after a long battle with depression. His ashes were scattered at Kirra Beach on the Gold Coast, one of the places he used to surf. For his mother it was a jolting, horrific introduction to the issue of suicide. Stung by the frustration of her own experiences in trying to get treatment for her son’s illness, Clark formed an organisation to create awareness about Australia’s suicide epidemic and to inspire action to treat it. It became known as the White Wreath Association.

The most recent figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show the grim reality of the problem: in 1998, 2683 people died of suicide in Australia (2150 males and 533 females). In the same period, 1731 people died in road accidents.

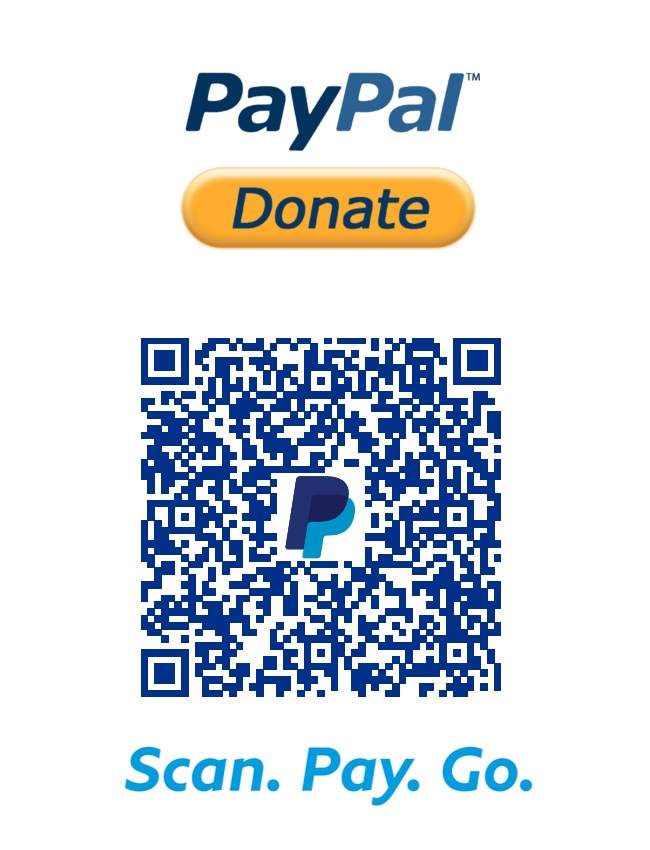

Clark organised the inaugural White Wreath Day in front of Parliament House, Canberra, on November 24, 1999. Both the Prime Minister, John Howard, and Opposition Leader Kim Beazley looked upon 2723 wreaths laid in memory of those who committed suicide in 1997.

“People look at these displays and they can’t believe what they see,” Clark says. “They can’t believe that each wreath represents a life lost in a year in Australia.

“I was probably like everybody else. I didn’t know what was happening with my son. When my son finally admitted, ‘Mum, I do need help’, there was just a sigh of relief. I thought, ‘Thank God, Jason, you’ve admitted you’ve got a problem.’ I felt so relieved, thinking, ‘Okay, you’ve admitted it, now we can get help.’

“But that was the beginning of the end, because of the lack of treatment, the lack of information, the lack of support. What I went through trying to get help, I wouldn’t wish upon anybody. I praised my son, because admitting you have a problem is extremely hard for people.”

But Clark says that when she and her son sought professional help, she was shut out. “If we wanted to be involved in any of his treatment, they said, ‘I’m sorry, Mrs Clark, Jason’s over 18, if he doesn’t want you to be there, we can’t involve you.’

“I said, ‘I’m his Mum, he’s living in our house, I want to help.” But I had no involvement whatsoever because of the confidentiality law.

“People don’t commit suicide,” she adds. ” ‘Commit’ is a murderous act. These people are suffering some form of mental illness. They’re not capable of making sane decisions like you and me. My son was a beautiful, handsome boy. You see him and think there’s nothing wrong with him, but it’s an illness of the mind. No sane person would kill themselves. A sane person wouldn’t even injure themselves. Their [depressed people’s] thoughts are distorted.”

This year’s White Wreath Day took place on Wednesday, November 8 in Canberra, where ALP parliamentarians Joel Fitzgibbon, the shadow minister for small business, and backbencher Craig Emerson laid a wreath for fallen colleague Greg Wilton, the former federal member for the Victorian seat of Isaacs who took his own life earlier this year after a protracted battle with depression. Also attending were Labor frontbenchers Dr Carmen Lawrence and Cheryl Kernot.