Flawed system failed Daniel at every turn.

Two years on, a young father’s unheeded cry for help haunts his family

Grieving: Joan Castree, left, with Whitney, 4, and her daughter, Jo-lene Castree, with Mykie, 2, and Aleshia, 4

Picture: SIMON O’DWYER

By CLAIRE HALLIDAY

Whitney and Aleshia were two years old when they found their father hanging in the garage. More than two years later, it’s an image that still disturbs the twins.

Their mother, Jo-lene Castree, 22, shares the memory of that day in January, 1999. That she felt sure the day would come hasn’t made it any easier to accept.

“I knew that Daniel was going to die but there was nothing I could do,” she says. Her husband, Daniel Chambers, was 22 when he committed suicide.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Daniel was just one of 2492 deaths that year attributed to “intentional self harm”.

Fanita Clark, Director and founder of the Brisbane based White Wreath Association, believes Daniel’s story is sadly typical.

This year, what began as a way to commemorate the 1999 death of Fanita Clark’s own son, Jason, 19, National White Wreath Day, on May 29, has been added to the national health events calendar.

The association has offices in Brisbane, Townsville, Perth and Melbourne and is implementing support in Sydney, Canberra and Hobart. In Geelong, Jo-lene’s mother, Joan Castree, 48, is the official contact and organiser of the local service.

Joan believes problems in the health system need to be changed. The attitude towards confidentiality issues, she says, is the main thing. “Getting Daniel help was totally impossible because they wouldn’t talk to any of us about his case. They couldn’t discuss his case with anyone else but him.”

In the midst of depressive or psychotic episode though, in which he would often smash windows and punch walls, Daniel was in no mood to come to the telephone.

On the day he died, Jo-lene was trying to get help from the mental health service. Told that his case couldn’t be discussed with her, she was asked to bring Daniel to the phone.

“He just laught at me. Just laughed at me and walked out to the garage. That was the last time I saw him,” Jo-lene says.

She remained on the phone, telling the person on the other end that she needed intervention, that her husband was going to kill himself. She said he had locked himself in the garage, hoping they would take her seriously.

“They told me people don’t go into a garage to kill themselves. They said he’d get in the car and leave the house if he was going to do it.”

The response from the police was just as frustrating. With Daniel’s past aggressive behavior already known to them, they told her to “leave the bastard”.

“That’s not what he needed. Daniel needed help,” Jo-lene says.

She was on the phone again when she heard a strange noise. “I walked into the garage and the girls were both hanging on to his legs and saying, ‘Daddy won’t move’.” She tried to get him down but couldn’t. “He was already dead anyway.”

Jo-lene believes Daniel was continually let down by the system. When police were called during a previous incident, the result was a court case a month before he died, with Daniel charged with resisting arrest. A combined sentence of community work and psychological counselling was agreed upon.

The next day Daniel was assigned community work, Jo-lene says. “But he never got his counselling.”

When he did get an assessment appointment two days before he died, Jo-lene says he was excited.

He was saying, ‘they’re going to fix me’,” she says. Instead, Daniel only saw a social worker. To Daniel, it seemed the final betrayal.

Despite stating his intention to commit suicide, he wasn’t categorised as high risk because he couldn’t tell the social worker when or how he intended to do it.

Although Jo-lene can’t guarantee he would still be alive today if things had been handled differently, she feels that Daniel would not have died as hi did – on that Saturday in the garage in her back yard. Her mother agrees.

“It’s a terminal illness,” Joan says. “Daniel’s trajectory towards death was so clear to anyone who knew him well.

“He was dying… He talked more and more of suicide. I’m not talking about cures. There’s no cure for cancer or AIDS but they prolong life and make the person comfortable and they are working towards a cure.

“They need to do the same for suicide, because it is a disease. The mind is ill. It shuts down its normal function and homes in on death.” Joan’s hope for this Tuesday, and future White Wreath Days, is that people left picking up their lives after a loved one’s suicide will realise they are not alone.

“If it had just happened to us I would say, ‘OK, we didn’t know how to work the system’, or that there was a breakdown in communication. But it’s not just us. A lot of suicide victims left behind have the story we have; that’s the real story.

“The government needs to spend just as much on suicide prevention as they do on anti smoking or road accidents. if you’ve got to wait 12 months, or even three weeks to get into counselling, that’s too long when someone is in crisis. If you can keep someone alive just enough to change the system, you can help.”

Even if time is slowly healing the scars, the memories continue to emerge. While Joan was picking her husband up from work recently, she heard a choking sound from the back seat and turned to see Whitney playing with a piece of colored ribbon, wrapping it around her neck. “She said, ‘If I put this around my neck I’ll go to heaven to be with Daddy’,” Joan says.

So, to counter their original stories of heaven as a wonderful place where “Daddy is happy”, Joan and Jo-lene have had to amend the fairy tale.

“I told her that if she goes to heaven she can never, ever come back to see mummy. That Daddy can’t ever come back, ” Joan says.

Aleshia seems to have realized it. “Last week she came in to me and told me that it was time she had a new daddy, so I told her to speak to her mother, ” Joan says. “She went to Jo-lene and said, ‘Mum, I’ve got to find a new daddy but please let him live long. I don’t want one that lives short’.”

On May 29 a service to mark National White Wreath Day will be held at Rosanna Baptist Church, Rosanna, at 10:30am. In Geelong, a service will be held in Johnstone Park at noon.

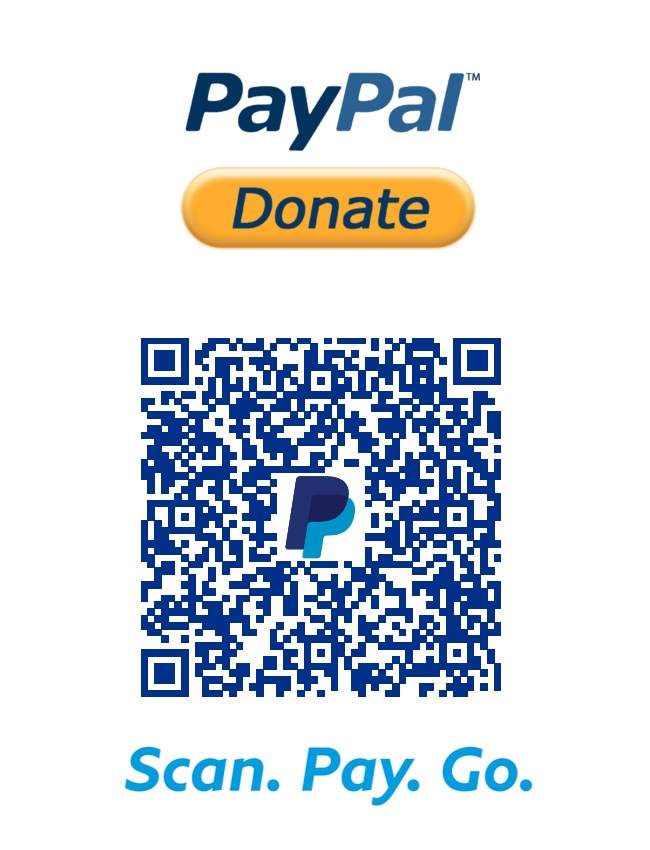

www.whitewreath.com

(White Wreath Association)